The best questions often stem from the inquisitive learner. As educators, we love, and are always humbled by, those moments when we get to say, “I don’t know.” For some of these questions, you may already know the answers. For others, you may never have thought to ask the question. For all, questions, comments, concerns, and critiques are encouraged. Welcome to the Kids Korner.

Explore This Issue

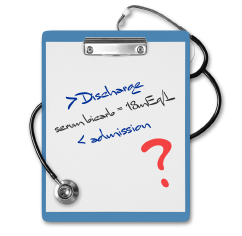

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 04 – April 2017Question 1: In children with acute gastroenteritis (AGE), is there a particular serum bicarbonate level that strongly predicts admission or outpatient treatment failure?

While most AGE literature evaluating serum bicarbonate focuses on its incorporation into assessment scores of dehydration, few studies evaluate its ability to predict hospital admission.

A prospective observational study evaluated 206 children with AGE between the ages of 1 month and 5 years. Of these kids, 59 of 206 (29 percent) had blood work drawn.1 The goal of the study was to assess the validity of the clinical dehydration scale (CDS), which classifies dehydration as “no,” “some,” or “moderate/severe” dehydration. The authors, a priori, grouped serum bicarbonate levels into two groups (< 18 and ≥ 18 mEq/L). In the group with “moderate/severe” compared to “some” dehydration, the serum bicarbonate was < 18 mEq/L in 75 percent versus 39 percent (P=0.22), respectively. This difference was not statistically significant, and there were only a very small number of “moderate/severe” dehydrated patients. The rate of admission was 5 percent (10 of 206), but no comparison was made between admitted and discharged patients. Overall, the study suggested that, as expected, children with worsening dehydration may have lower serum bicarbonate levels.

ILLUSTRATION: Chris Whissen PHOTOS: shutterstock.com

Another prospective observational study by Madati and Bachur evaluated 130 children age 3 months to 7 years with AGE.2 Patients received either blood work or an end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) reading. Per the authors, an ETCO2 of 31 mmHg approximates a serum bicarbonate of 15 mmol/L. In this study, they also confirmed that an ETCO2 of 31 mmHg or less had 98.6 percent sensitivity for demonstrating a serum bicarbonate of ≤16 mmol/L. Regarding admission, they found there was no significant difference in serum bicarbonate values (P=0.11) between patients admitted (17.5 ± 3.3 mmol/L) versus discharged (19.0 ± 3.1 mmol/L). Twelve percent of the patients were admitted.

A study by Freedman et al may best address this topic.3 It’s a secondary analysis of prospectively collected data. In the initial study, the authors were looking at regular versus rapid rehydration. Children were randomized to either a single 20 mL/kg bolus or three boluses (total of 60 mL/kg) over the course of an hour. The primary outcome was whether a serum bicarbonate level could predict an ED revisit within seven days. The study included 226 children older than 3 months of age with AGE and found that 52 of 226 (23 percent) were admitted at the time of initial presentation. Of the remaining discharged patients, 30 of 174 (18 percent) had an ED revisit within seven days. There was no statistically significant difference (P=0.25) between serum bicarbonate values in children who did and did not have a “successful discharge” (not admitted at initial visit and not having a return ED visit within seven days).

Conclusion: While the data are limited, there does not appear to be a particular serum bicarbonate level that can reliably predict hospital admission in children with acute gastroenteritis.

Question 2: Should prepubescent children with acute epididymitis receive antibiotics?

The majority of studies addressing pediatric epididymitis are retrospective and exclude postpubertal or sexually active children. Therefore, this topic does not address these populations. To begin, let’s look at some representative retrospective studies.

A three-year retrospective study by Sakellaris and Charissis reviewed 66 cases of acute scrotum in preadolescent Greek boys, of which 29 were diagnosed with epididymitis.4 Boys with epididymitis were ages 2–13 years and diagnosed with epididymitis via ultrasound (n=28) or intraoperatively (n=1). All patients with acute epididymitis received intravenous antibiotics, and all received follow-up. There were no positive urine cultures and no follow-up complications of testicular atrophy.

Another retrospective study examined 151 cases of first-time epididymitis in children presenting to an outpatient urology clinic.5 Ages ranged from 3 months to 17 years. Cases of recurrent epididymitis, recent instrumentation or urologic surgery, or epididymitis secondary to another cause (eg, testicular torsion, vasculitis, hernia, etc.) were excluded. Of note, this study included postpubertal boys. Ninety-seven patients were treated as inpatients. All patients received a scrotal ultrasound (US). Urinalysis (UA) was obtained in 93 of 151 (61.6 percent) patients, and of those 93 patients, there was only one positive urinalysis. The authors describe this case as “mild leukocyturia,” although their definition of mild leukocyturia could not be found. The urine culture was negative in that child. With regard to the remainder of these 93 patients, a urine culture was obtained in only six patients. All patients received antibiotics, but follow-up data are not mentioned. This article suggests that the large majority of epididymitis cases demonstrate negative UA results. Two additional retrospective studies demonstrate similar findings.6,7 A recent systematic review of 27 retrospective studies by Cristoforo that included 1,496 total pediatric patients also concluded that practitioners “should consider prescribing antibiotics only in the treatment of acute epididymitis for patients with a confirmed bacterial etiology.”8

There are two observational prospective studies. The first evaluated prepubertal boys, excluding postpubertal or sexually active patients.9 Of the 48 boys included, five (10.4 percent) had a positive UA, defined as > 3 WBC/hpf, or a positive urine culture. All of those with a positive culture had a positive UA. The remaining 43 cases of epididymitis were diagnosed by US only (n=1), radionuclide scan only (n=36), a combination of the two modalities (n=3), or an “experienced clinician” (n=3). Of these 43 remaining cases, 36 (83.7 percent) did not receive antibiotics, and 40 (93 percent) received follow-up. No patients showed any negative effects of epididymitis, with the authors suggesting “antibiotics play little or no role in its management when there are no urinary findings.”

A second prospective study was a one-year prospective study in prepubescent males and excluded sexually active boys.10 The patients were 2–14 years of age. All patients with epididymitis (n=44) were diagnosed via US and admitted. Only 3 of 44 (6.8 percent) received antibiotics, with the remainder receiving “analgesics and bed rest.” All patients were followed up through symptom resolution. Only three patients had “mild pyuria” (3–5 WBC/hpf), and one patient had a positive urine culture. The authors state, “During follow up, no testicular abnormality and no symptom recurrence were noted.”

Conclusion: In prepubescent boys with acute epididymitis, antibiotics are probably not routinely indicated unless the UA or urine culture is positive. In postpubertal or sexually active boys with epididymitis, antibiotics treatment may be practitioner-specific since many studies on acute epididymitis commonly exclude these patients.

Dr. Jones is assistant professor of pediatric emergency medicine at the University of Kentucky in Lexington.

Dr. Jones is assistant professor of pediatric emergency medicine at the University of Kentucky in Lexington.

Dr. Cantor is professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics, director of the pediatric emergency department, and medical director of the Central New York Poison Control Center at Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, New York.

Dr. Cantor is professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics, director of the pediatric emergency department, and medical director of the Central New York Poison Control Center at Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, New York.

References

- Goldman RD, Friedman JN, Parkin PC. Validation of the clinical dehydration scale for children with acute gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):545-549.

- Madati PJ, Bachur R. Development of an emergency department triage tool to predict acidosis among children with gastroenteritis. Pediatr Emerg Car. 2008;24(12):822-830.

- Freedman SB, DeGroot JM, Parkin PC. Successful discharge of children with gastroenteritis requiring intravenous rehydration. J Emerg Med. 2014; 46(1):9-20.

- Sakellaris GS, Charissis GC. Acute epididymitis in Greek children: a 3-year retrospective study. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167(7):765-769.

- Graumann LA, Dietz HG, Stehr M. Urinalysis in children with epididymitis. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2010;20(4):247-249.

- Santillanes G, Gausche-Hill M, Lewis RJ. Are antibiotics necessary for pediatric epididymitis? Pediatric Emerg Care. 2011;27(3):174-178.

- Joo JM, Yang SH, Kang TW et al. Acute epididymitis in children: the role of the urine test. Korean J Urol. 2013;54(2):135-138.

- Cristoforo TA. Evaluating the necessity of antibiotics in the treatment of acute epididymitis in pediatric patients: a literature review of retrospective studies and data analysis (published online ahead of print Jan. 17, 2017). Pediatr Emerg Care.

- Lau P, Anderson PA, Giacomantonio JM, et al. Acute epididymitis in boys: are antibiotics indicated? Br J Urol. 1997;79(5):797-800.

- Somekh E, Gorenstein A, Serour F. Acute epididymitis in boys: evidence of a post-infectious etiology. J Urol. 2004;171(1):391-394.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Treatment for Acute Gastroenteritis, Acute Epididymitis in Pediatric Patients”