The Case

A 45-year-old man is brought to the emergency department with a toe injury. The patient states he was at a cookout drinking alcohol when he developed pain in his great toe and noticed bleeding while walking. He stumbled and thinks he stepped on a broken piece of glass. He denies any other injuries or loss of consciousness. He is intoxicated with a Glasgow Coma Score 14–15 (for slight verbal disorientation at the time), is slightly agitated but redirectable, and has stable vital signs. Examination of his toe shows tenderness to palpation without deformity, and there are no signs of neurovascular compromise. His injury is shown in Figure 1. A radiograph is negative for fracture or foreign body. What do you suspect happened?

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 07 – July 2021Describing and Classifying Wounds

From a forensic and mechanistic perspective, traumatic injuries can be divided into two categories: blunt trauma and sharp force trauma. Blunt trauma results from an impact with a dull, firm surface or object. Injuries can be patterned (ie, the characteristics of the wound suggest a particular type of blunt object) or nonspecific. Blunt trauma is typically caused by contact with a solid, firm surface (floor or ground) or with an object (such as a fist, bat, or bottle). Sharp force trauma describes an injury produced by an instrument with a thin edge or point (ie, sharp cutting implements).

Blunt trauma injuries include abrasions, bruises/contusions, hematomas, avulsions, fractures, and lacerations. Sharp force injuries include stab wounds, incised wounds, and cuts. Even though lacerations and cuts both involve a break in the skin, they are not synonymous, and the terms should not be used interchangeably. Most emergency physicians and clinicians use the term “laceration” incorrectly to mean any break in the skin, especially one that requires closure, but it really only applies to those skin breaks that are the result of blunt force trauma or contact with an object. Though they may appear similar, especially if they are linear, they are mechanistically different. Here’s why being precise with these terms, and using the strict definitions, can help documentation, especially for forensics purposes.

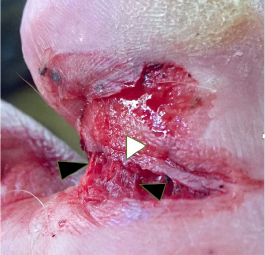

Figure 1: Wound on right great toe depictinged irregular wound edge (white arrowhead) and tissue bridging (black arrowheads).

Lacerations are sustained via two mechanisms: crushing and tearing. Crush lacerations occur when tissue is compressed between two objects with enough force to cause skin breakage. Lacerations are usually full thickness and are seen when the skin and soft tissue are crushed between the impacting object and underlying bone. Lacerations are often linear but can be irregularly shaped. Blood vessels and nerves can be exposed. The wound edges of a laceration are frequently irregular, bruised, or macerated. Such wounds may be contaminated. Delicate tissue bridges can be seen within the depth of the wound. In fact, tissue bridging is the hallmark finding in lacerations. In cuts, these tissue bridges are disrupted by the sharp edge of the weapon.

Split lacerations occur when tissue is stretched at two points resulting in splitting or tearing at the weakest point in between. This mechanism is classically seen in genital trauma following sexual assault. The wound edges of split lacerations may not exhibit damaged wound edges and may not include tissue bridging.

Sharp force wound edges are characteristically sharp, clean, unbruised, unabraded, and inverted. There is no tissue bridging, and the injuries tend to be more linear. The deeper tissues are cut cleanly in the same plane. Stab wounds are deeper than their length or width and occur when a sharp object is thrust into the skin. Incised wounds and cuts are greater in width and/or length than depth and occur when a sharp implement is dragged over the skin surface.

Documentation Tips

When describing open wounds in the emergency department, there are some important historical key points that need to be considered:

- Mechanism of injury

- Type of injury: blunt trauma, sharp force trauma, or both

- Area of the body injured

- Object causing injury: type, size, other characteristics (ie, clean or contaminated)

- Social factors: consistency of wounds or injuries seen with the history provided

After obtaining a thorough history, each wound should be closely inspected and documented. The more precise the wound description, the clearer it will be to future chart readers. Wound descriptions should include the precise location, relationship to key body landmarks, size, shape, directionality, patterned appearance, and any other unique characteristics. The presence of any debris, bleeding, or foreign matter should be noted.

When documenting the size of a wound, a ruler or other measurement device should be used. Most cotton tip applicator packages have a ruler imprinted on the packaging. Whenever possible, at least two measurements should be documented, length and width, length and depth, or all three. Some implements used for stab wounds have unique characteristic patterns that can be imparted into the skin surface. Any of these hallmark patterned wounds should be described. Forensic experts may be able to match the wound pattern to the weapon that caused it.

Wounds should be documented using both narrative descriptions and graphic representations using electronic medical record (EMR)–embedded body diagrams and/or uploaded digital photographs of the patient’s injuries. EMR-embedded body diagrams are often used to highlight wound location and shape but may make accurate wound representation difficult compared to written charts. Digital photographs, on the other hand, provide an accurate representation of the wound and memorialize findings for future review by other clinicians and experts, plus they may be useful in any potential legal proceedings. Most current EMRs allow images to be uploaded securely, creating easy storage and access.

Case Resolution

Based on your examination, you feel the wound is consistent with a laceration, although the mechanism is uncertain. The patient’s wife later arrives and states he was walking down the patio steps when he stumbled, struck his toe against the edge of the step, cried out in pain, and began bleeding. The wound is irrigated, and its characteristics are documented. The wound is sutured, and the patient is discharged with return precautions and follow-up instructions for suture removal.

Dr. Riviello is chair and professor of emergency medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Dr. Rozzi is an emergency physician, director of the Forensic Examiner Team at WellSpan York Hospital in York, Pennsylvania, and chair of the Forensic Section of ACEP.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Use Accurate Wound Terminology When Describing Injuries”