This medical malpractice case is high yield for every emergency physician as it covers a subtle but life-threatening diagnosis and highlights the importance of communication at multiple levels. It also provides an opportunity for us to better understand the nuances of EMTALA-related litigation.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 12 – December 2020The Case

A 30-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a chief complaint of weakness and ankle pain. He was seen in an outpatient clinic and referred to the emergency department for evaluation. The patient had recently returned from a surfing trip to Asia. While on the trip, he reported being bitten by mosquitos multiple times but had not taken any malaria prophylaxis. He also had jumped out of a truck the day before and had twisted his left ankle.

The review of systems was positive for fever, vomiting, myalgias, and headaches.

He was otherwise healthy and up-to-date on his vaccinations.

Figure 1

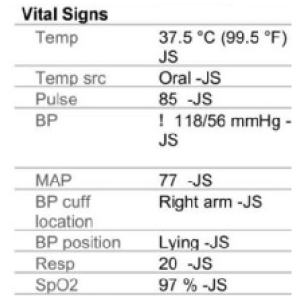

His triage vitals showed a temperature of 99.5ºF, heart rate of 85 bpm, blood pressure of 118/56, respirations of 20 per minute, and oxygen saturation of 97 percent on room air (see Figure 1).

A boilerplate normal examination was documented, including a musculoskeletal note describing “no edema and no tenderness.”

The physician noted a differential of “viral syndrome, otitis media, pharyngitis, pneumonia, gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection, and others.”

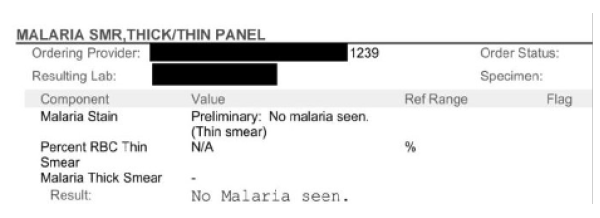

A complete blood count (CBC) was ordered and showed leukocytosis of 14.9, thrombocytopenia of 132. The differential showed 87 percent neutrophils and 5 percent lymphocytes. The comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) was entirely unremarkable. The urinalysis showed a large amount of blood and occasional bacteria but no white blood cells, leukocyte esterase, or nitrites. An influenza swab was negative, and a malaria smear was also negative (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

An ankle X-ray was ordered and showed “moderate soft tissue swelling” but no fracture or dislocation.

A repeat set of vitals was ordered, and everything was in the normal ranges.

Given the lack of emergency findings and normal vitals, the patient was discharged home. The doctor recommended he take Tylenol or ibuprofen, stay hydrated, and rest. Crutches were provided, and instructions were given to keep the left ankle elevated. A plan to follow up with urgent care the following week for reassessment was recommended.

Commentary

Everything about this case seems straightforward to this point. There is nothing that can be reasonably criticized. The workup is negative.

But this is a medical malpractice column. There has to be a twist.

Recall that the patient was seen in an outpatient clinic and referred to the emergency department. The ED physician was unaware of this. The patient did not volunteer this information, there were no triage notes mentioning it, and no one asked the patient about the preceding medical care.

Shortly before ED arrival, the outpatient clinic documented a blood pressure of 81/38 and a temperature of 100.2ºF.

The Case Continues

After being discharged, the patient had an uneventful night. The next morning, he began to feel worse, and two days after the initial visit, he returned to the emergency department. His exam was now notable for “significant edema” at the left ankle, with bruising up the leg. Extreme tenderness was noted, but there was no crepitus.

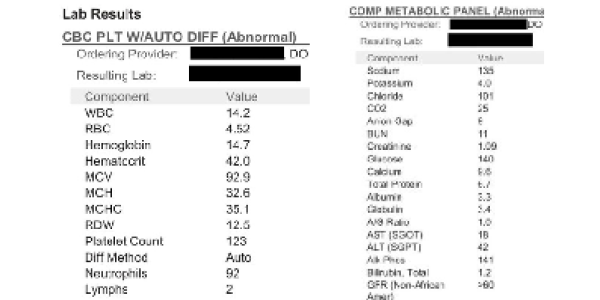

Vital signs were notable for slight tachycardia at 105 bpm, though his blood pressure, respirations, and pulse remained normal. His CBC and comprehensive metabolic panels were essentially unchanged (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

He was diagnosed with cellulitis and admitted to the hospital due to the severity of the swelling, bruising, and pain. The patient had a penicillin allergy listed and was started on vancomycin monotherapy. The emergency physician wrote a long note, including the reasoning shown below:

Consideration for necrotizing fasciitis was done however there is nothing on patient’s exam or history to assess that this is present. Patient’s had leg pain now for a couple of days and this has not been rapidly worsening the patient did state that it got significantly worse today. Pain is not out of proportion. Patient hasn’t had any significant fever and white blood cell count is not significantly elevated.

In the hospital, the patient developed renal failure, and his vitals worsened. A surgeon was consulted, and the patient was taken to the operating room. There was purulent drainage from the leg, and small areas of necrotic muscle were identified.

The patient was ultimately transferred to a larger medical center. He underwent several repeat operations for necrotizing fasciitis, ultimately requiring several skin grafts leading to permanent disability of his left leg.

The Lawsuit

The patient filed a lawsuit against the hospital. The plaintiff’s attorney alleged EMTALA violations, and therefore the lawsuit was filed in federal court. The specific claim was that the medical screening exam violated EMTALA because it did not lead to the correct diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis.

The judge ultimately dismissed the lawsuit. In his opinion, he noted that “EMTALA is not a medical malpractice statute, and failing to correctly diagnose Plaintiff’s illness does not give rise to [EMTALA] liability.” This concept was reiterated throughout his opinion, and elsewhere he stated, “Defendants cannot incur EMTALA liability for what is merely an incorrect diagnosis.”

The patient proceeded to sue the hospital and all of the doctors involved in the case in state court. That lawsuit was eventually withdrawn without any mention of a settlement.

Discussion

This case highlights the essential role that communication plays in the care of all patients. The disconnect in the patient’s referral at the first ED visit nearly led to a disaster. Awareness of his prior hypotension certainly would have led to a higher level of concern—though not necessarily the correct diagnosis; given his benign workup and vital signs in the emergency department, he may have been discharged home regardless. That the doctor did not realize the patient was referred to the emergency department from an outside facility illustrates the concept of “holes in the Swiss cheese” remarkably well. The clinic did not call the emergency department to notify them of a referred patient, there were no processes in place requiring the triage nurse to ask patients if they had been referred to the emergency department by an outside facility, the patient did not volunteer this information, and the doctor did not think to ask.

This case provides an excellent opportunity to refine our understanding of EMTALA. Just because a medical screening exam does not arrive at the correct diagnosis does not mean there was an EMTALA violation. The hospital and emergency physicians involved seem to have prevailed in the legal proceedings, but caution must be taken given the complexity of EMTALA litigation. Specialized attorneys may spend large swaths of their careers dealing with these cases, and even the most well-intentioned emergency physicians are unlikely to have read, let alone understand, its complexities. Just as in medicine, nuanced interpretations are best left to the experts.

See the Records

Visit www.medmalreviewer.com/case-7-ankle-injury/ to review the full medical records or send Dr. Funk an email with your thoughts on the case at admin@medmalreviewer.com.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “What Is—and Isn’t—Guaranteed Under EMTALA Can Be Complex”