There are always times when our attempts to educate individual patients on evidence-based medicine fall short. This leads to a range of acceptable practice variation, with each clinician making their best judgment regarding the care of a patient. This variation is on impressive display with respect to the management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP).

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 10 – October 2020The options for treatment of PSP range from hospitalization after the placement of a large-bore chest tube to outpatient management with naught but close follow-up. These could all be considered reasonable options absent high-quality data regarding the safety of any individual approach. But recently, researchers have provided several pieces of clarifying evidence.

The management of an otherwise stable but symptomatic patient with PSP typically boils down to a few key decisions. First, is any intervention required? Secondly, if so, what sort of invention: standard chest tube, narrow-bore chest tube, or aspiration? Finally, should a patient be discharged home or remain in the hospital for observation?

Historical Data

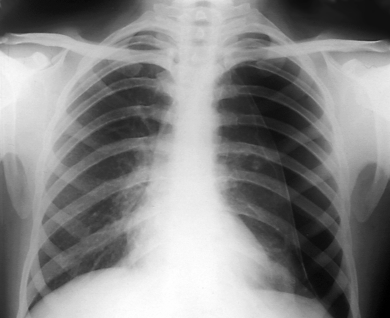

Frontal chest X-ray of a patient with a pneumothorax.

Zephyr / Science Source

The historical data are best summarized in an Annals of Emergency Medicine article by Mummadi et al, who recently performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis.1 These authors collated 12 studies, accounting for 781 patients, and applied statistical techniques in an attempt to compare three strategies for intervention: large-bore chest tube (≥14 French), narrow-bore (<14 French), or needle aspiration. The authors defined the success of a strategy in terms of resolution of symptoms, adequate lung re-expansion, and the ability for discharge from the emergency department.

Following the applicable statistics, the authors reached only one solid conclusion: the large-bore chest tube is clearly the least preferable of the options. Within the bounds of their combined small sample, the large-bore tube was certainly successful at management. However, that strategy was also associated with higher complication rates than the equally successful but safer narrow-bore tube. Needle aspiration, on the other hand, was neither obviously superior nor inferior. The latter strategy lacked the immediate success of the others, primarily due to diminished re-expansion, but had the advantage of being associated with far fewer complications than its competitors.

New Data

Published in the months following that review, however, two additional trials comprising 552 patients have now been added to this sparse body of evidence, providing further insight. The first of these trials is arguably the more important of the two.2 In that study, the authors effectively presumed the adequacy of a small-bore chest tube and compared it against conservative management. In perfectly stark terms, “conservative management” means “do nothing,” with only a hint of hyperbole.

Patients were eligible for this trial if they had moderate to large pneumothoracies, defined as at least 32 percent collapse, calculated on chest radiography. In the intervention group, patients underwent placement of a ≤12 French Seldinger-style chest tube, were rechecked after four hours, and could have the chest tube removed and be discharged if demonstrating clinical and radiological improvement. In contrast, patients in the comparison group were simply observed for four hours for clinical or radiologic deterioration, and, if none occurred, were discharged home. In this trial, the primary endpoint was resolution of the pneumothorax by eight weeks, but all patients had in-person assessments at frequent intervals in the interim.

As it turns out, “doing nothing” is nearly as good as, and maybe even better than, doing something. Of those randomized to conservative management, 84.6 percent completed follow-up without undergoing a procedure for their pneumothorax. At the eight-week follow-up for the primary outcome, 94.4 percent of those managed conservatively had full lung re-expansion, compared with 98.8 percent of those who underwent intervention. However, this small advantage in radiographical resolution is offset by multiple resource- and patient-oriented outcomes favoring conservative management. Those who underwent an invasive procedure spent more days in the hospital; underwent more chest radiographs; required more days off work; and, potentially more importantly, had twice the pneumothorax recurrence rate within 12 months, 16.8 percent versus 8.8 percent. These long-term observations, even as a secondary outcome, probably tip the scales toward conservative management.

That said, not all patients were able to be discharged following an initial attempt at conservative management. This leads us to the second trial.3 This trial took a bit of a different tack, testing a specific small-bore ambulatory device against treatment, which follows guidelines by the British Thoracic Society (BTS).4 BTS guidelines permit the treating clinician to perform an aspiration procedure, place a small-bore chest tube, or both. The primary outcome in this trial was length of hospital stay within 30 days.

As might be expected, those randomized to the strategy placing an emphasis on the ambulatory device had dramatically fewer days in the hospital. Two-thirds of those randomized to ambulatory management were able to be discharged on the day of presentation as compared to one-third otherwise. Clinicians attempted aspiration in two-thirds of those randomized to standard care, but half of those were ultimately managed with a chest tube and hospital admission. During the month of follow-up, recurrences were greater in those undergoing guideline-based standard care, as was the need for any additional procedures.

The interpretation of this trial is a bit muddier than the first. Whereas patients in the first trial could undergo chest tube placement and removal and be subsequently discharged, that was not an option in the standard care arm in the second trial. Then the ambulatory management cohort also recorded more adverse events than the standard care arm, 55 percent to 39 percent, including all of the serious adverse events. Fortunately, none of the serious events included death or significant disability but nonetheless lead to reasonable framing of the ambulatory strategy as a balance of competing risks and benefits.

Conclusions

Combining all the evidence from the systematic review and these trials, a few consistent points appear to emerge. The vast majority of patients presenting with a primary spontaneous pneumothorax do not need to be hospitalized but can be safely managed as outpatients following initial assessment and interventions, if indicated. If an intervention is necessary, the smallest-bore chest tube is preferred, and this may include a strategy in which a patient is discharged with devices designed for ambulatory management in place. Most important, these data indicate that nonintervention strategy is sound and reasonable in many instances. The pneumothoracies included for evaluation were large, representing nearly 65 percent of the hemithorax, yet still demonstrated uncomplicated recoveries. In an otherwise appropriate patient with a stable, non-enlarging pneumothorax, the best intervention may be the lack thereof.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of Dr. Radecki and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer or academic affiliates.

References

- Mummadi SR, de Longpre J, Hahn PY. Comparative effectiveness of interventions in initial management of spontaneous pneumothorax: a systematic review and a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(1):88-102.

- Brown SGA, Ball EL, Perrin K, et al. Conservative versus interventional treatment for spontaneous pneumothorax. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(5):405-415.

- Hallifax RJ, McKeown E, Sivakumar P, et al. Ambulatory management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10243):39-49.

- MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65 Suppl 2:ii18-31.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

One Response to “What’s the Best Intervention for Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax?”

October 25, 2020

Gary GechlikI think the Thora-Vent is an excellent device, straight forward to utilize, a very flat learning curve, you prepare the area, locally anesthetize, and place the Thora-vent with the Trochar. I recommend watching a video a number of times before performing the procedure as a review. That is a common technique in many industries to review a less utilized procedure as a double check to maintain a high quality of outcome.