My last shift started with a 3-year-old with a dog bite to the face, a 10-year-old with a forearm injury, and an anxious 16-year-old who needed a lumbar puncture. When working with children and young adults, we are constantly looking for ways to make the emergency department visit more tolerable for all involved. There are two things that have helped me come closer to that goal. The first is having child life specialists. The second is intranasal medication delivery.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 10 – October 2015Initially created for local nasal effects, intranasal medications have become a desired route for certain drugs when seeking a systemic effect. Some immunizations have found success using the intranasal method, and several other medications have followed suit, namely those used for sedation and analgesia. There are several benefits to using the intranasal route, including:

- High vascularization of the nasal mucosa

- Wide absorption area

- Avoidance of first-pass metabolism by the gastrointestinal or hepatic pathways

- Avoidance of IV placement

- High patient tolerance of the drug administration

- Quick onset of action1

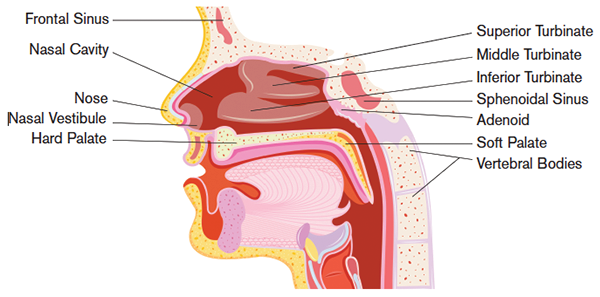

The nasal fossa is divided into three parts: the vestibule, the cavity, and the turbinates (see Figure 1). The turbinates are classified into the inferior, middle, and superior. The main site for systemic drug entry is around the inferior turbinate due to its high surface area and vascularization.

There are several factors that may play into the effectiveness of intranasal drug delivery, including volume administered, particle diameter, spray administration, factors influencing the site of absorption (eg, other drugs such as phenylephrine), nasal blood flow, and mucociliary clearance and medical conditions that affect it, and these things should be taken into account when administering intranasal medications.2 The best absorbed medications have low molecular weights, are highly lipophilic, and have no net charge at physiologic pH.3

The most basic is the drip method, but this does require a compliant child to achieve success. Probably the most widely used device is the mucosal atomizer.

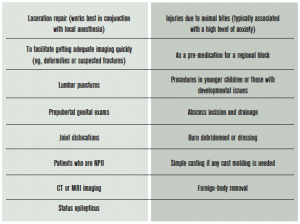

Intranasal delivery has been used for several different purposes including vaccinations; treatment of certain conditions such as rhinosinusitis, seizures, migraines, and diabetes insipidus; antipsychotic medications; and sedation and analgesia.4 For purposes of this article, we will focus on sedation and analgesia. Historically, two main classes of drugs have been used in intranasal administration: opioids and benzodiazepines (see Table 1 for dosing guidelines). More recently, other drugs, such as ketamine and dexmedetomidine, have also been studied.

Medications to Use

Midazolam is a useful drug in pediatrics for situations where you need anxiolysis and amnesia. It can be given in a variety of ways, and intranasal use has been widely studied. Doses ranging from 0.2 mg/kg to 0.5 mg/kg have been evaluated. Overall, it has been shown to have a rapid onset of action and achieve adequate sedation, and it is associated with high parent satisfaction. One consistently found drawback is that intranasal was more irritating than other routes of administration.3 One study evaluated using intranasal lidocaine as a premedication and found that its use helped prevent the burning that is often associated with the use of intranasal midazolam.5 Further prospective studies have been done, and preliminary data (ahead of publication) show similar results. Intranasal midazolam is a great choice when you need something to take the edge off but analgesia is not your main focus. I find that it works best in situations where my analgesia is managed by other means, typically topical anesthetics and/or regional blocks. Its mild amnestic properties are also helpful when it comes to potential follow-up.

Fentanyl is the ideal intranasal medication, highly lipophilic and low molecular weight. It has been shown to be more effective than intravenous morphine for pain reduction in long bone fractures.3 It is very well tolerated overall and produces adequate analgesia. It has recently been compared with intranasal ketamine and found to be equally analgesic but have fewer side effects (mainly dizziness), although they were mild overall.6 This is a great choice when you need analgesia quickly and you don’t know if you’ll need an IV or if they need to be NPO. I use this routinely before getting imaging in my orthopedic patients.

Other agents for sedation and analgesia have also been assessed. Intranasal ketamine has been evaluated in the emergency department as well as in the pre-hospital setting. Doses ranging from 0.5 mg/kg to 9 mg/kg have been used with adequate sedation.3 Further studies need to be done to establish the ideal dose in the pediatric patient. Intranasal dexmedetomidine was evaluated in an observational study and showed good sedation and image quality when it was used for sedation for computed tomography scans in children.7

Delivery

Delivering intranasal medications can be done in a few different ways. The most basic is

Figure 2. Mucosal atomization device

the drip method, but this does require a compliant child to achieve success. Probably the most widely used device is the mucosal atomizer. It screws on to the top of your medication syringe, and when you spray it into the nare, it rapidly distributes the particles after breaking them down into smaller ones that are more easily absorbed (see Figure 2).3

Intranasal medication delivery can be a useful tool when dealing with children (see Table 2 for suggestions on when to consider intranasal delivery). Some tips that will allow for greater success include:

- Consider suctioning prior to administration if there is a lot of mucus present.

- Use small volumes .

- Use the highest concentration of medication available and do not dilute.

Use both nares to increase surface area Intranasal medications are a quick, safe, and relatively painless way to deliver analgesia and anxiolysis to pediatric patients. They are a great resource to have in your tool kit!

Dr. Sorrentino is professor of pediatrics in the division of emergency medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dr. Sorrentino is professor of pediatrics in the division of emergency medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

References

- Fortuna A, Alves G, Serralheiro A, et al. Intranasal delivery of systemic-acting drugs: small-molecules and biomacromolecules. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2014;88:8-27.

- Grassin-Delyle S, Buenestado A, Naline E, et al. Intranasal drug delivery: an efficient and non-invasive route for systemic administration: focus on opioids. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;134:366-379.

- Del Pizzo J, Callahan JM. Intranasal medications in pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:496-504.

- Kaminsky BM, Bostwick JR, Guthrie SK. Alternate routes of administration of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49:808-817.

- Chiaretti A, Barone G, Rigante D, et al. Intranasal lidocaine and midazolam for procedural sedation in children. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:160-163.

- Graudins A, Meek R, Egerton-Warburton D, et al. The PICHFORK (pain in children fentanyl or ketamine) trial: a randomized controlled trial comparing intranasal ketamine and fentanyl for the relief of moderate to severe pain in children with limb injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65:248-255.

- Filho EM, Robinson F, de Carvalho WB, et al. Intranasal dexmedetomidine for sedation for pediatric computed tomography imaging. J Pediatr. 2015;166:1313-1315.

- Tsze DS, Steele DW, Machan JT, et al. Intranasal ketamine for procedural sedation in pediatric laceration repair. Ped Emerg Care. 2012;28:767-770.

- Yuen VM, Hui TW, Irwin MG, et al. A randomized comparison of two intranasal dexmedetomidine doses for premedication in children. Anaesthesia. 2012;67:1210-1216.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

No Responses to “When to Use Intranasal Medications in Children”