Case: A 21-month-old girl presents after a witnessed fall off a chair onto a tile floor. She hit her head and cried immediately. There was no loss of consciousness, and she vomited once. She has a frontal hematoma, and her parents are concerned about a serious head injury.

Question: Can emergency physicians be trained to use point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) to rule in or rule out skull fractures in children?

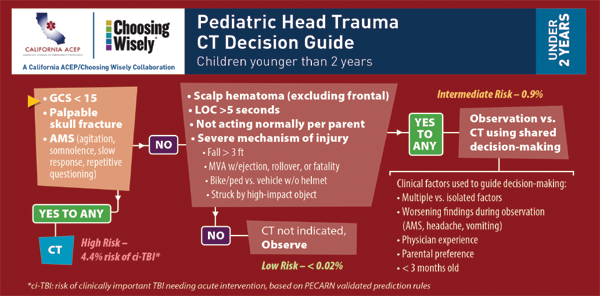

Background: Children fall, hit their head, and often present to the ED. There has been a push to decrease exposing young brains to ionizing radiation. Decision rules such as the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) computed tomography (CT) head rules (see Figure 1, and visit California ACEP’s website for more tools for implementing the PECARN algorithm) help reduce the number of CT scans done on patients with minor head injury. However, the presence of skull fractures is associated with a more than four times increased risk of an intracranial injury.

Ultrasound has been found to have good accuracy when performed by clinicians for various types of fractures.1 POCUS has been found to be equal or superior to plain films and even bone scans involving fractures of some flat bones like the sternum.2,3 Thus, it makes sense to consider the use of POCUS to identify skull fractures in children.

Several authors have investigated using POCUS for diagnosing pediatric skull fractures. The sensitivities from these studies range from 82 percent to 100 percent and specificity from 94 percent to 100 percent.1,4,5

Relevant Article: Rabiner JE, Friedman LM, Khine H, et al. Accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound for diagnosis of skull fractures in children. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e1757-1764.

- Population: Patients 21 years old or younger presenting to the ED with suspected skull fracture undergoing CT scan.

- Intervention: POCUS in the ED. Physicians received a 60-minute training session (a 30-minute didactic session to learn how to use ultrasound to evaluate the skull for fracture and a 30-minute hands-on practical session).

- Comparison: CT scan.

- Outcome: Test characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, +LR, and -LR).

Authors’ Conclusions: “Clinicians with focused ultrasound training were able to diagnose skull fractures in children with high specificity.”

When used along with a clinical decision instrument like PECARN, POCUS can be a useful adjunct for detecting skull fractures and further risk-stratifying minor head injuries.

Key Results: There were 69 children suspected of having a skull fracture in this study, with a mean age of 6.4 years. The prevalence of fracture was 12 percent (8/69).

- Sensitivity 88 percent

(95 percent CI, 53–98 percent) - Specificity 97 percent

(95 percent CI, 89–99 percent) - Positive predictive value 0.78

(95 percent CI, 0.45–0.94) - Negative predictive value 0.98

(95 percent CI, 0.91–1.0) - Positive likelihood ratio 26.7

(95 percent CI, 6.7–106.9) - Negative likelihood ratio 0.13

(95 percent CI, 0.02–0.81)

EBM Commentary: This is the largest single study looking at the topic of POCUS for diagnosing pediatric skull fractures. However, it still was a rather small study as demonstrated by the wide 95 percent confidence intervals.

There was a single false-negative patient (missed fracture) who had a fracture adjacent to the hematoma. The authors describe the patient with the missed fracture as only requiring observation and no specific treatment.

There were two false positives in the study. One false positive was by a novice scanner but was over-read as negative by a more senior clinician. This suggests training may be important to ensure accuracy. The second false positive was reported positive by both physicians reading the scan, which was not noted on CT. However, CT is not a 100 percent sensitive test either, and the patient may have had a true positive on ultrasound and false negative on CT.

Bottom Line: Emergency physicians can be taught POCUS to identify pediatric skull fractures with high specificity. When used along with a clinical decision instrument like PECARN, POCUS can be a useful adjunct for detecting skull fractures and further risk-stratifying minor head injuries. However, serious intracranial injuries can occur without fracture, and the sensitivity of ultrasound for fracture is not yet sufficient to use it as the sole method for detecting injury and making treatment and disposition decisions.

Case Resolution: Instead of ordering a CT, you decide to use POCUS to look for a skull fracture and combine this with the PECARN rule.

Mom is able to hold her daughter on her lap while you gently scan over and around the frontal hematoma. You are not able to identify a fracture. The parents are reassured and happy to avoid doing a CT scan at this time. The child is observed for a few hours in the ED as per the PECARN rule. They are discharged home with clear instructions to return if the clinical picture changes.

Thanks to Greg Hall, MD, who is faculty member at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and part of the Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine group, for his help with this review.

Remember to be skeptical of anything you learn, even if you learned it on the Skeptics’ Guide to Emergency Medicine.

Dr. Milne is chief of emergency medicine and chief of staff at South Huron Hospital, Ontario, Canada. He is on the Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine faculty and is creator of the knowledge translation project the Skeptics’ Guide to Emergency Medicine (www.TheSGEM.com).

References

- Weinberg ER, Tunik MG, Tsung JW. Accuracy of clinician-performed point-of-care ultrasound for the diagnosis of fractures in children and young adults. Injury. 2010;41:862-868.

- Jin W, Yang DM, Kim HC, et al. Diagnostic values of sonography for assessment of sternal fractures compared with conventional radiography and bone scans. J ultrasound Med. 2006; 5:1263-1268.

- You JS, Chung YE, Kim D, et al. Role of sonography in the emergency room to diagnose sternal fractures. J Clin Ultrasound. 2010;38:135-137.

- Riera A, Chen L. Ultrasound evaluation of skull fractures in children: a feasibility study. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:420-425.

- Parri N, Crosby BJ, Glass C, et al. Ability of emergency ultrasonography to detect pediatric skull fractures: a prospective, observational study. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:135-141.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

2 Responses to “When to Use Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Skull Fractures”

October 8, 2015

Kenn GhaffarianSensitivity in the article is misquoted at 8%. Should read 88%.

October 8, 2015

Dawn Antoline-WangThank you, we have corrected the error.