We just learned lessons about our preparedness (or lack thereof) in detecting and managing one virus in the form of Ebola, and now we have another? Now it seems, along with everything else, emergency physicians must function as frontline epidemiologists, identifying potentially dangerous infections. Welcome to the new millennium of emergency medicine.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 04 – April 2016Zika Basics

Zika virus, a flavivirus transmitted mainly by mosquitos, is another in a line of emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) making new or return appearances in the United States. Zika can also be spread sexually (although the ease of transmission is not known) and through blood transfusions (a particular problem in outbreak areas). Most areas of South America, Central America, and Mexico are currently experiencing the largest known outbreak of Zika viral infection. To date, more than 150 cases of Zika have been detected in the continental United States. Current data suggest that at least nine of these cases (5.8 percent) are in pregnant women. All of these have been travel related in people returning from outbreak areas. About 107 endemic (locally transmitted) cases acquired by mosquito bites have been reported in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. In outbreak areas, the proportion of the population infected varies from 70 percent to 1.2 percent based on multiple factors. The vector mosquitos required to transmit Zika are already endemic in the South, Midwest, and Eastern United States. The World Health Organization predicts that Zika will likely be endemic in most of the United States within two years.

Zika is related to dengue, Chikungunya, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, and tickborne encephalitis. It usually causes a mild disease resulting in only rare hospitalizations or deaths. However, during the current outbreak, some very astute physicians in Brazil noted a sharp increase in the number of births with severe microencephaly.

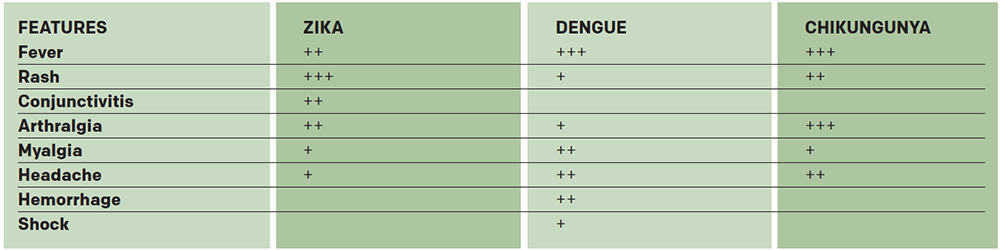

The symptoms of Zika include macular or papular rash (90 percent), subjective fever (65 percent), arthralgia (65 percent), conjunctivitis (55 percent), myalgia (48 percent), cephalgia (45 percent), retro-orbital pain (39 percent), dependent edema (19 percent), and vomiting (10 percent). The presence of conjunctivitis and absence of hemorrhage are the most useful clinical indicators in differentiating Zika from dengue and Chikungunya infections (see Table 1). Zika causes minimal disease, with only one in five infected people developing symptoms. Other viral diseases such as dengue and yellow fever are also moving into the United States and are of much greater clinical concern, except for the question of pregnancy.

Does Zika infection cause fetal malformations? In Brazil, the incidence of microencephaly is not clearly known. However, during the current outbreak, observations suggest a possible 20-fold rise in this malformation over previous years. Some of the children with microencephaly tested positive for Zika; some did not. Although there is no absolute confirmation of a link between Zika and fetal malformations, the latest report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) greatly strengthens the theory. However, the circumstantial evidence is concerning enough that multiple agencies have issued alerts to people living in or planning to travel to Zika outbreak areas. Additionally, increasing incidences of Guillain-Barre syndrome have been reported in the Zika outbreak areas. The CDC is also investigating this potential association. No link has yet been confirmed, but as with any viral syndrome later developing neurologic findings, this entity should be considered.

(click for larger image) Table 1. Differential Diagnosis Based on Clinical Presentation of Three Emerging Flaviviral Diseases

Source: CDC

Testing and Treatment

Treatment of Zika is entirely symptomatic. No vaccine exists for Zika. Vaccines for other flaviviruses (yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, tickborne encephalitis, and dengue) are available but are of no benefit in Zika. Several companies are working on a Zika vaccine. Because the primary concern is in pregnancy, additional burden is placed on vaccine creators to ensure the safety and efficacy for the mother and fetus. It is probable that a vaccine is at least two years away, but it will likely be longer.

Testing is available for Zika through the CDC and should be performed based on the most current guidelines provided by that agency. Pregnant women who have a travel history to an outbreak area should be tested. All Zika testing is done through state or local departments of health and should be coordinated through those agencies. In settings where the clinician is considering testing outside of the above recommendation, consultation with the state or local epidemiologist on call is indicated. The assay is specific for Zika immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies. Such antibodies are detectable between four days and 12 weeks following infection. The results are available within one to two weeks. A positive test only means that the Zika IgM antibody has been detected. It says nothing about the clinical condition of the patient or fetus or the risk of a fetus developing a malformation. False-positive tests are possible after a recent infection with a related flavivirus or in people who have received yellow fever or Japanese encephalitis vaccines. This means that a positive Zika IgM test must be confirmed by other testing at the CDC. Any positive test is an indication for careful referral of pregnant patients to obstetrics/gynecology and patient counseling as outlined by the CDC.

According to news reports, several rapid assays are being developed for Zika. Some test for Zika RNA rather than IgM. Although there is enthusiasm in the lay press, substantial obstacles must be surmounted before rapid RNA testing for Zika can become a reality. Rapid tests historically have proven to be somewhat problematic, particularly once the test is released from study conditions and put in the hands of clinicians. In some scenarios, the presence of DNA or RNA of a particular virus or bacterium has little or no correlation with clinical disease. Getting a rapid result can reduce anxiety. However, it’s likely that rapid results will need to be confirmed by other methods at the CDC. There is no specific treatment for Zika infection. Immediate results may be desirable but are not critical to Zika management. Much will depend on the cost and accuracy characteristics of rapid tests when they are developed.

As is true of most issues in medicine, the primary task for the clinician is educational rather than medical. This includes educating not just our patients but also ourselves and the staff at our facilities. EIDs will continue to be a serious issue for this and the next generation of emergency physicians. Although not as clinically dramatic, Zika represents a significantly greater risk to the health of our patients than the recent Ebola outbreak due to the risk of fetal abnormalities. Travel history outside of the United States or to specific outbreak areas should be a routine part of the ED intake process. The Zika virus outbreak is another opportunity for EDs to be educators, refine our approach to EIDs, and enhance the health of our communities.

Dr. Hogan is director of the TeamHealth National Academic Consortium and director of education at the TeamHealth West Group.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

One Response to “Zika Virus Transmission, Testing, and Treatment Information You Need to Know”

May 8, 2016

David MorganExcellent update.